In a business with fluid dynamics between customers, drivers, and merchants, real-time data helps make crucial decisions which grow our business and delights our customers. Machine learning (ML) models play a big role in improving the experience on our platform, but models can only be as powerful as their underlying features. As a result, building and improving our feature engineering framework has been one of our most important initiatives in improving prediction accuracy.

Given that many predictive models are typically trained with historical data, utilizing real-time features allows us to combine long-term trends with what happened 20 minutes prior, thereby improving prediction accuracy and customer experiences.

At DoorDash, we are working to increase the velocity and accessibility of the feature engineering life cycle for real-time features. Our strategy involved building a framework that allows data scientists to specify their feature computation logic and production requirements through abstract high-level constructs, so feature engineering is accessible to a broader user base among our ML practitioners.

Leveraging the Apache Flink stream processing platform, we built an internal framework, which we call Riviera, that allows users to declaratively specify their feature transformation from source(s) to features stores through a simple configuration.

An overview of feature engineering at DoorDash

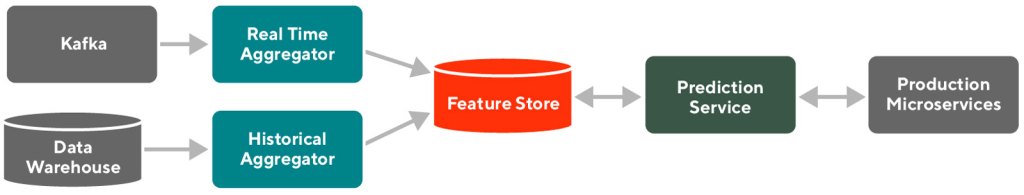

Within DoorDash’s ML Platform, we have worked on establishing an effective online prediction ecosystem. Figure 1, below, gives a high-level overview of our ML Infrastructure in production. We serve traffic on a large number of ML Models, including ensemble models, through our Sibyl Prediction Service. Because the foremost requirement of our prediction service is to provide a high degree of reliability and low latency (<100 ms), we built an efficient feature store to serve aggregated features. We use Redis to power our gigascale feature store to provide high throughput and availability for our features.

Currently, the ML models that power DoorDash primarily use batched features. These features are constructed from long running ETLs, and as such represent aggregations from historical data. However, as outlined in our previous article, we have been gradually trending towards features aggregated from real-time streaming sources because the value derived from such real-time features provides significant improvements to our existing models, and opens up newer avenues for model development. For our initial launch around real-time features, we constructed our feature engineering pipelines as a native Flink application and deployed them for predictions to our Redis-backed serving store.

Building feature engineering pipelines in Flink

While this status quo was stable and sufficient when we began our transition to real-time features, it soon became a bottleneck to accelerated feature development. The three main issues with our existing infrastructure involved accessibility, reusability, and isolation of real-time feature pipelines.

Accessibility

Flink as a programming paradigm is not the most approachable framework, and has a reasonable learning curve. Updating a native Flink application for each iteration on a feature poses barriers to universal access across all teams. In order to evolve into a more generally available feature engineering solution, we needed a higher layer of abstraction.

Reusability

Much of Flink code and its application setup is often a boilerplate, which is repeated and rewritten across multiple feature pipelines. The actual business logic of the feature forms a small fraction of the deployed code. As such, similar feature pipelines still end up replicating a lot of code.

Isolation

To make managing deployments of multiple feature pipelines easier, different feature transformations are often bundled together into a single Flink application. Bundling feature transformations provides simpler deployment at a cost of having inefficient resource management and a lack of resource isolation across the feature pipelines.

We recognized that a declarative framework that captures business logic through a concise DSL to generate a real-time feature engineering pipeline could remedy the inefficiencies described above. A well-designed DSL could enhance accessibility to a wider user base, and the generation process could automate boilerplate and deployment creation, providing reusability and isolation. Using a DSL for feature engineering is also a proven approach for ML platforms, as shown by Uber’s Michelangelo Palette and Airbnb’s Zipline.

As we already used Flink stream processing for feature engineering, Flink SQL became a natural choice for our DSL. Over the last few years, Flink SQL has seen significant improvement in its performance and feature set thanks to contributions from Uber, Alibaba, and its open source community. Given these improvements, we are confident that Flink SQL is mature enough for us to build our DSL solutions.

Challenges to using Flink SQL

While we established that Flink SQL as a DSL was a good approach to build a feature engineering framework, it posed a few challenges for adapting to our use cases.

- No abstraction for underlying infrastructure: While Flink SQL works as a DSL to express feature transformation logic, we still need to provide additional abstraction to hide the complexity of the underlying infrastructure. The feature engineering framework needs to provide seamless support for a variety of evolving connectors like Kafka and Redis.

- Adaptors to support Protobuf in SQL processing: To enable SQL processing, the data needs to have a schema and be converted to Flink’s Row type. Flink has built-in support for a few data formats that can be used in its SQL connectors, with Avro being one example. However, at DoorDash most of the data comes from our microservices, which use gRPC and Protobuf. To support Protobuf in SQL processing, we needed to construct our own adaptors.

- Mitigate data disparity issues: While we can rely on Protobuf to derive the schema of data, the schema and data producers may not be optimally defined for feature construction. Some source events in our Kafka sources contain only partial data, or spread the relevant feature attributes across multiple events that need to be joined. In the past, we tried to mitigate this problem by creating a global cache in Flink’s operator chain, where the missing attributes can be looked up from past events from different sources. Flink SQL would need to adapt these schema quality issues as well.

With these challenges in mind, we will dive into our design of our Flink-as-a-service platform and the Riviera application, where these challenges are addressed in a systematic way.

An overview of the Flink-as-a-service platform

To help build sophisticated stream processing applications like Riviera, it is critical to have a high-quality and high-leverage platform to increase developer velocity. We created such a platform at DoorDash to achieve the following goals:

- Streamline the development and deployment process

- Abstract away the complexities of the infrastructure so that the application’s users can focus on implementing their business logic

- Provide reusable building blocks for applications to leverage

The following diagram shows the building blocks of our Flink-as-a-service platform together with applications, including Riviera, on top of it. We will describe each of the components in the next section.

DoorDash’s customized Flink runtime

Most of DoorDash’s infrastructure is built on top of Kubernetes. In order to adopt Flink internally, we created a base Flink runtime docker image from the open source version. The docker image contains entry point scripts and customized Flink configurations (flink-conf.yaml) that integrate with DoorDash’s core infrastructure, providing integrations for metric reporting and logging.

DoorDash’s Flink library

Because Flink is our processing engine, all the implementation for consuming data sources and producing to sinks needs to be Flink native constructs. We created a Flink library that provided a high level abstraction of a Flink application encapsulating the common streaming environment configurations, such as checkpoints and state backend, as well as providing Flink sink and source connectors commonly used at DoorDash. Applications that extend from this abstraction will be free from most of the boilerplate configuration code and do not need to construct sources or sinks from scratch.

Specifically for Riviera, we developed components in our platform to construct source and sink with a YAML configuration and generic Protobuf data format support. We adopted YAML as the DSL language for capturing the configuration because of its wide adoption and readability.

To hide the complexity of source and sink construction, we designed a two-level configuration: infrastructure level and user level. The infrastructure level configuration encapsulates commonly used source/sink properties which are not exposed to the user except for the name as an identifier. In this way, the infrastructure complexities are hidden from the end user. The user level configuration uses the name to identify the source/sink and specify its high level properties, like the topic name.

For example, an infrastructure-level YAML configuration for a Kafka sink may look like this:

sink-configs:

- type: kafka

name: s3-kafka

bootstrap.servers: ${BROKER_URL}

ssl.protocol: TLS

security.protocol: SASL_SSL

sasl.jaas.config: …

... The user-level configuration will reference the sink by name and may look like this:

sinks:

- name: s3-kafka

topic: riviera_features

semantic: at_least_onceWe built support for Kafka as a source, and S3, Kafka, and Redis as sinks.

For Flink serialization and deserialization schemas, we support both Protobuf and Avro. As mentioned before in our challenges, Protobuf is the de facto serialization format for events published from microservices, but there is no built-in Flink SQL support for it. We solved this obstacle by creating a reflection based deserialization layer that infers, flattens, and translates every Protobuf into a tabular data stream for consumption in the Flink application. For example, the following protobuf schema would translate into a flattened sparse table schema with (id, has_bar, has_baz, bar::field1, …, baz::field1, … ).

message Foo {

int64 id = 1;

oneof sub_event {

Bar bar = 2;

Baz baz = 3;

}

}To leverage this Protobuf support, all the user needs to do is provide a Protobuf class name as a source configuration.

In the near future, we plan to leverage the new feature in Confluent’s schema registry, where Protobuf definition is natively supported as a schema format and eliminates the need to access Protobuf classes at runtime.

Creating a generic Flink application in Riviera

Building on issues with Flink that needed to be addressed and the existing state of our infrastructure, we designed Riviera as an application to generate, deploy, and manage Flink jobs for feature generation from lean YAML configurations.

The core design principle for Riviera was to construct a generified Flink application JAR which could be instantiated with different configurations for each feature engineering use case. These JARs would be hosted as standalone Flink jobs on our Kubernetes clusters, which would be wired to all our Kafka topics, feature store clusters, and data warehouses. Figure 3 captures the high-level architecture of Riviera.

Once we built a reasonable chunk of the environment management boilerplate into the Flink library, the generification of Riviera’s Flink application was almost complete. The last piece of the puzzle was to put the sink, source, and compute information into a simplified configuration.

Putting it all together

Let’s imagine we want to compute a store-level feature that provides total orders confirmed by a store in the last 30 minutes, aggregating over a rolling window that refreshes every minute. Today, such a feature pipeline would look something like this:

source:

- type: kafka

kafka:

cluster: ${ENVIRONMENT}

topic: store_events

schema:

proto-class: "com.doordash.timeline_events.StoreEvent"

sinks:

- name: feature-store-${ENVIRONMENT}

redis-ttl: 1800

compute:

sql: >-

SELECT

store_id as st,

COUNT(*) as saf_sp_p30mi_order_count_avg

FROM store_events

WHERE has_order_confirmation_data

GROUP BY HOP(_time, INTERVAL '1' MINUTES, INTERVAL '30' MINUTES), store_id

A typical Riviera application extends the base application template provided by our Flink library, and adds all the authentication and connection information to our various Kafka, Redis, S3, and Snowflake clusters. Once any user puts together a configuration as shown above, they can deploy a new Flink job using this application with minimal effort.

Case study: Creating complex features from high-volume event streams

Standardizing our entire real-time architecture through the Flink libraries and Riviera have yielded really interesting findings on the scalability and usability of Flink SQL in production. We wanted to present one of the more complex use cases we have encountered.

DoorDash’s Delivery Service defines a Protobuf schema for a DeliveryEvent, which records a wide variety of delivery states. These states record different phases of a delivery, such as delivery creation, delivery pickup, and delivery fulfillment, and are accompanied with their own state data. Our parsing library flattens this schema out to a sparse table schema with over 300 columns, and Flink’s Table Environments are able to deal with it extremely efficiently.

Some aggregate features on this data stream can be fairly simple in terms of maintaining the state for the stream computation. For example, “Total created deliveries in the last 30 minutes” can be a useful aggregate over store IDs, and can be handled by rolling window aggregates. However, we have some feature aggregations that require more complex state management.

One example of such a feature that requires more state is what we call “Delivery ASAP time”. ASAP for a delivery tracks the total time from an order’s creation to its fulfillment. In order to track “Average ASAP for all deliveries from a store in the last 30 minutes”, the delivery creation event would need to be matched with a delivery fulfillment event for every delivery ID, before aggregating it against the store ID. Additionally, the data schema provides store IDs and delivery IDs only during the creation events, but only store IDs for the fulfillment events. Because of this choice for the source data, the computation would need to solve the data disparity issue and carry forward the store ID from creation events for the aggregation.

Before Riviera, we managed the state lookup for a delivery by maintaining an in-memory cache within the Flink application that cached event time and store ID for creation events, and emitted the delta for a store ID when a matching fulfilment event occurred.

With Riviera we were able to simplify this process and make it more efficient, as well, using SQL interval joins in Flink. The query below demonstrates how Riviera creates this real-time feature:

SELECT st, AVG(w) as daf_st_p20mi_asap_seconds_avg

FROM (

SELECT

r.store_id as st,

r.delivery_id as d,

l.proctime as t,

(l.event_time - r.event_time) * 1.0 as w

FROM (

SELECT delivery_id,

`dropoff::actual_delivery_time` as event_time,

_time as proctime

FROM delivery_lifecycle_events

WHERE has_dropoff=true

) AS l

INNER JOIN (

SELECT `createV2::store_id` as store_id,

delivery_id,

`createV2::created_at` as event_time,

_time as proctime

FROM delivery_lifecycle_events

WHERE has_create=true

) as r

ON l.delivery_id=r.delivery_id

AND r.proctime BETWEEN l.proctime - INTERVAL '4' HOUR and l.proctime - INTERVAL '1' MINUTES)

GROUP BY st, HOP(t, INTERVAL '1' MINUTES, INTERVAL '20' MINUTES)Semantically, we run two subselect queries, with the first representing fulfillment events with their delivery_id and dropoff_time, and the second representing the creation events with delivery_id, store_id, and creation_time. We then run a Flink interval join on those sub queries to compute the ASAP for each delivery and aggregate over all stores.

This approach not only reduced our complex state maintenance to a few lines of SQL, it also helped achieve a much higher degree of parallelism. In order to maintain a cache in the original solution, we needed the processing to have a parallelism of 1 on a beefy node, but since Flink can maintain join state more efficiently, we were able to parallelise the computation to 15 workers and optimize it with much smaller pod sizes. Currently, the self join can handle over 5,000 events per second with 300 columns self joined over a period of four hours with ease.

Production results

The launch of Riviera enabled feature development to become more self-serve and has improved iteration life cycles from a few weeks to a few hours. The plug-and-play architecture for the DSL also allows adapting to new sources and sinks within a few days.

The integration with the Flink-as-a-service platform has enabled us to automate our infrastructure by standardizing observability, optimization, and cost management behind the Flink applications as well, allowing us to bring up a large number of jobs in isolation with ease.

The library utilities we built around Flink’s API and state management have reduced codebase size by over 70%.

Conclusion

The efforts behind Riviera hold a lot of promise for democratizing real-time processing at DoorDash. The work behind it provides a general framework not just for creating real-time features, but also for generic real-time processing of raw events. We’ve been able to utilize Riviera to generate real-time business metrics for consumption by various dashboarding and analytics endpoints as well. The ability to deploy complex Flink applications via SQL-based DSL is a good foundation for achieving this.

As we grow adoption and consumers, we hope to add many missing links to this framework to improve its value and usability. We plan to work on deployment automations and make it possible to debug and visualize the output of SQL statements before a new Riveria job is deployed. We will expand the use cases of Riviera to more complicated stream joins and find ways to autoscale them. Stay tuned for our updates and consider joining us if this type of work sounds interesting.

Acknowledgements

Thanks goes out to the team including: Nikhil Patil, Sudhir Tonse, Hien Luu, Swaroop Chitlur Haridas, Arbaz Khan, Hebo Yang, Kornel Csernai, Carlos Herrera, and Animesh Kumar.